- Breadcrumbs

- Blog

- Artist Profile

- Claude Monet and Impressionism

Claude Monet and Impressionism

Origins of Impressionism

In mid-19th century France, the art world was dominated by the Salon, a prestigious annual exhibition controlled by academic authorities who favored polished, detailed paintings of historical, mythological, or religious themes. This traditional system rejected many emerging artists who sought to represent the modern world and its fleeting moments. The emphasis was on idealized perfection rather than capturing life as it is seen and felt.

Against this backdrop, a group of innovative painters began to question these rigid standards. Their focus shifted to everyday life, the effects of natural light, and the atmosphere of a moment rather than exact detail. When the 1874 independent exhibition opened just weeks before the official Salon, it presented a striking contrast. Visitors encountered artworks that seemed hastily executed with loose brushwork and unfinished forms, which many found shocking or even laughable.

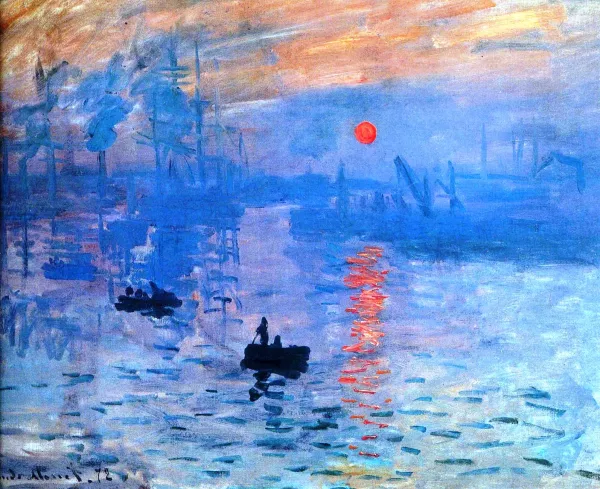

One of the most talked-about works was the harbor scene Impression, Sunrise, whose title inspired the label "Impressionists". A contemporary critic, Louis Leroy, published a mocking review in Le Charivari, imagining a conversation with an imaginary academic painter exasperated by the new style's lack of finish:

What? Impression? You said it. I’m of the opinion that Impression is the name of a wallpaper in its embryonic state.

Rather than rejecting the jab, the artists embraced the name—turning what was intended as ridicule into a banner of artistic freedom and innovation. This mix of humor and outrage set the tone for the movement’s ongoing challenge to the art establishment, marking the first clear break from tradition and the start of modern painting.

Impression, Sunrise (1872)

Claude Monet's Impression, Sunrise portrays the port of Le Havre at dawn, with the sun's glow reflected on water in loose, rapid brushstrokes. Monet aimed to capture the fleeting sensations of light and atmosphere rather than a detailed landscape. This painting, shown in the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874, sparked the name “Impressionism” after a critic mockingly used its title to describe the new, freer approach to painting. Though initially derided, Impression, Sunrise has become one of Monet's most famous works and a symbol of the movement’s break from tradition.

Impression Sunrise Oil Painting, Claude Monet

Impressionist Exhibitions

Frustrated by the restrictive official Salon exhibitions, a group of artists including Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, and Degas staged independent shows starting in 1874. These exhibitions showcased works painted with a new focus on personal perception, everyday scenes, and changing natural light, challenging academic norms and promoting freedom of brushwork and color, even if met initially with skepticism.

The independent exhibitions continued regularly, with eight shows held between 1874 and 1886 in various Parisian venues. These salons were crucial in allowing this group of artists to display their work on their own terms, free from the unpredictable and often rejecting judgments of the official Paris Salon. This new platform gave the artists full control over which paintings were exhibited, allowing them to present their radical new vision cohesively and repeatedly.

While the inaugural exhibition in 1874 attracted about 3,500 visitors, it was met with mixed reactions. Critics mostly dismissed the works as unfinished sketches or amateurish experiments. Yet among the crowd were collectors and dealers who began to recognize the groundbreaking quality of the paintings. Over subsequent exhibitions, the group’s financial situation improved, partly through the patronage of influential collectors like Gustave Caillebotte and the support of dealers such as Paul Durand-Ruel.

The exhibitions also fostered a sense of camaraderie and collectiveness. Each show included painters who would later become iconic, including Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, Degas, and Cézanne. While not every work in these shows was Impressionist in style—some leaned toward Realism or Pre-Impressionism—the collective spirit and shared goal of capturing modern life linked them.

Despite ongoing criticism throughout the 1870s and early 1880s, these exhibitions laid the foundation for the acceptance of Impressionism. By 1886, the eighth and final exhibition marked both an end and a triumph, as the movement gained momentum and began to reshape the art world.

Monet's Painting Techniques

The hallmark of Monet’s art lies in his groundbreaking techniques, which broke with long-established traditions of studio painting. Central to his approach was a dedication to capturing the immediate sensory experience of a scene — the way light changed with the passing hours, how colors interacted in natural settings, and how fleeting atmospheric conditions shaped perception. His use of rapid brushstrokes, vivid unmixed colors, and outdoor painting allowed him to portray the world not as a precise, fixed image but as an ever-shifting play of light and color. These techniques fundamentally redefined the possibilities of painting, influencing countless artists and marking Impressionism as a radical new movement.

En Plein Air Work

Painting en plein air—literally "in the open air" — was central to the innovative approach embraced by Monet and his contemporaries. Instead of working solely from sketches or memory in studios, this method involved setting up an easel outdoors to capture subjects directly from nature. It enabled artists to observe and respond immediately to shifting light, weather, and atmosphere, lending their works a fresh and spontaneous quality.

Though plein air painting was not Monet’s invention, he elevated it to a revolutionary level. The invention of portable oil paints in tubes during the 19th century freed artists from carrying heavy pigment blocks and messy grinding tools, making quick, onsite painting practical. This allowed capturing moments that could change rapidly—the warm glow of sunrise or the cool shadows on a riverbank—often working on several canvases at once as the scene’s mood evolved.

This approach demanded speed and decisiveness. Ever-changing sunlight required capturing impressions in short bursts. Monet famously used this method for his series, including haystacks and Rouen Cathedral, exploring transient natural effects under different conditions.

Painting outdoors came with challenges—weather, insects, and wind tested even the most dedicated. These hardships were embraced as part of the creative process, adding vitality and immediacy to the art. Immersed in nature, Monet translated not just form and color but the fleeting sensations of presence in a moment.

This en plein air technique became a defining feature of Impressionism, perfectly reflecting the movement’s core values - spontaneity, perception, and celebrating everyday natural scenes. It remains a foundational practice for landscape artists worldwide.

Light and Color

Rather than meticulously blending colors on the palette, Monet applied pure, broken brushstrokes side by side on the canvas. This technique allows the eye to mix colors optically rather than physically, creating vibrant effects of light and shadow that shift depending on the viewer’s perspective and the surrounding illumination. The approach conveys a sense of movement and life, capturing the constantly changing atmosphere.

Monet’s sensitivity to subtle shifts in daylight is evident across many of his works, from tranquil coastal scenes to his iconic series like the Haystacks and Water Lilies. He was fascinated by the way natural light altered the color and mood of an object throughout the day and seasons. By painting the same subject multiple times under different lighting conditions, he explored this dynamic interplay, revealing how perception changes with light.

This exploration of color was both scientific and poetic. Monet sought to record not only the colors he observed but the way light itself could become the main subject of a painting. Rather than defining edges sharply, he let colors dissolve into each other, creating a shimmering effect that mimics the softness and complexity of natural light.

His palette was deliberately limited yet vibrant, often focusing on complementary colors to intensify luminosity and contrast. By placing reds next to greens or blues beside oranges, the colors seemed to glow, enhancing the emotional impact of the scene.

Through these methods, light transcended being a mere visual element and became an expressive force that defined space and form. Monet’s groundbreaking use of light and color profoundly influenced Impressionism and laid the foundation for modernist movements focused on perception and abstraction.

The Impressionist Circle

Peers and Collaborations

While Monet's vision was deeply personal, he worked closely with contemporaries like Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille. Together, this circle shared interests in modern life and sought new ways to represent perception and fleeting moments. Their camaraderie fostered innovation and reinforced the principles of Impressionism.Enduring Influence of the Movement

Monet remains the most prolific and influential Impressionist artist. His dedication to capturing nature as it appears to the eye opened paths toward modern art movements emphasizing perception and abstraction. Impressionism transformed the art world, shifting attention from polished representation to experiential truth - an impact that resonates today.***

In summary, Claude Monet’s pioneering spirit and artistic innovations were instrumental in founding the Impressionist movement. Through his daring departure from academic traditions — embracing outdoor painting, broken brushwork, and a vibrant exploration of light and color — he captured the ephemeral beauty of the natural world like never before. Alongside his fellow Impressionists, Monet challenged conventions by presenting personal impressions of modern life, forever changing the course of art history. Today, his legacy endures not only in his timeless masterpieces but also in the continued influence of Impressionism on artists worldwide, inspiring new generations to see and depict the world with fresh eyes.